The Churn

The ATLien Reminding Folks To Read Poetry This Black History Month

Butter ATLFebruary 11, 2022

“All right, ain’t nothing we ain’t; we don’t need to be quiet no more about setting the trend for everything.”

The first time I met Aurielle Marie, or just Elle as I’ve come to know her, was in 2014, within a crowd of thousands marching downtown. Pulsing with energy, chants, signs, and emotion, we gathered in front of Atlanta’s CNN center to protest the injustice of Michael Brown’s killing, as well as to call out what we felt was the media network’s biased coverage of the events. We were outside their building, thousands deep, yet not a second of coverage had taken place.

Aurielle’s voice was within the mixture of both seasoned, veteran activists and newly engaged community organizers who seized the crowd’s attention. I watched as she turned a bullhorn into a weapon for justice, and captivated the crowd with her command of words. At the time we didn’t know we were actively making Black history, joining in a nationwide movement against police violence that still pulses today. But over the years we’ve accepted just how much those moments have come to shape who we are.

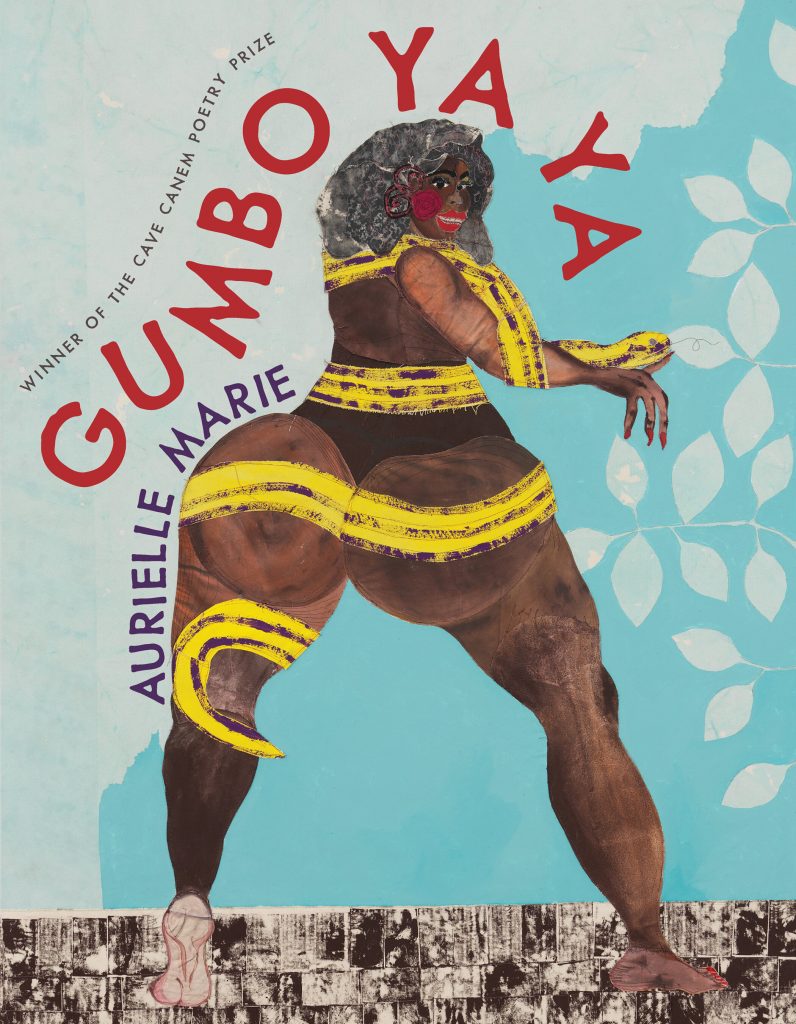

From meetings with high profile politicians and fiery stand-offs with local leaders, to now dozens of published writings, art performances, workshops, and lectures, Aurielle has truly become an Atlanta-bred force to be reckoned with on many fronts. Rejecting single labels like “activist” or “poet,” she calls herself a “cultural strategist,” and after recently reading Gumbo Ya Ya, her beautiful, award-winning collection of poetry published October 2021 by the University of Pittsburgh Press, I’m convinced even “cultural strategist” is too limited of a phrase to capture the depth of her work.

I sat down with Aurielle to talk all things poetry, her new book, and how her love for Atlanta and the experiences she’s had in this one-of-a-kind city have shaped her.

Check out the full interview below, and when you’re done, go ahead and add the book to your shopping cart.

Devyn: Just to start off, could you just tell me a little bit about yourself? Who you are, what you do, and how you arrived at making this poetry book?

Aurielle: Well, my name is Aurielle Marie. For the most part, my work is in investigates the social and political undertones of Black culture, which is everything from the now, the current, the trending — what’s on our timelines, what the memes are about, what we see on TikTok — and going as far back as hip-hop, the Civil Rights Movement, Black communal history, all that stuff.

Devyn: Sounds like a real, true cultural worker.

Aurielle: A cultural worker, yeah. I’m born and raised in Atlanta, and so all of my work is thinking critically about the South, because it’s my first love. And especially in my poetry, I think Southern poets are so slept on, and also so necessary. We really be at the forefront, quietly. So my work is real loud of course, because I’m like, “All right, ain’t nothing we ain’t; we don’t need to be quiet no more about setting the trend for everything.”

Devyn: So if a reader was not familiar with you or your work at all, and they just saw the very striking cover image on Gumbo Ya Ya, opened it and started reading it, what is it saying to that reader?

Aurielle: I love that you mentioned the cover because what I was trying to do was send a signal to people who may not one consider themselves poetry readers or the “target audience” for most poetry. I wanted to grab them and be like, “Hey, I am actually talking to you. This is actually for you.”

Because most people seeing books on bookshelves around the city are probably like, “Why is there a fat ass on this lady’s cover? What’s what’s going on in that book?” If I can intrigue them enough to open it, I think from the jump Gumbo Ya Ya will make it clear that Black Southern folks, Black queer people, Black trans folks, and Blackity-black Black girls are the target audience, at the expense of white comfort and white fragility. Which is not to say I don’t love and appreciate a white reader — hi, hello, and thank you if you’ve bought my book. But if there is a reader who’s not Black, saw the cover, opened the book and is excited about what’s happening, then they understand they’re in a practice of de-centering themselves as they’re reading the book, because it is Black folks who are centered.

Everyone reading the book is kind of trying on what it looks like to center Black women, and celebrate us, and acknowledge and accept our expanse, and the spectrum that we exist on. Sometimes, depending on who the reader is, that’s at the expense of their comfort or what they’re used to.

Devyn: That’s a really thorough overview of the cover; now tell me about the title, Gumbo Ya Ya.

Aurielle: I’m Creole, my family is Creole. And I know there’s this understanding of gumbo as a soup, and that’s the dominant thing. When you say “gumbo”, somebody’s like, “You need a rue, you need some crab, some chicken, and that’s from Louisiana.” It’s a really familiar term, however, “gumbo ya ya” is actually not a food-related term. It’s a cultural term. It’s a Creole term from the Gulf [Coast].

The best way I can describe it is when you are in a room with a whole bunch of people you ain’t seen in a minute. There’s that kind of home, everyone’s talking to everyone else. There’s conversations overlapping. You and I are deep in the convo, but then somebody calls you from across the room, so you’re talking to them while talking to me, and just that kind of hum of aliveness is gumbo ya ya. It’s like a soup of noise.

I think that term, that idea, is a great metaphor for what it means to be Black and a femme, specifically in the South and in the world. There’s just a lot of intersecting noise, a lot of things grabbing our attention and so many intersections that we’re trying to navigate, while keeping our focus. In that way the title itself is a sort of idea. But for the most part, I just wanted it to be a reminder of how alive we are and how much noise we navigate, with finesse, with beauty, with flex — with all of our parts.

Devyn: One thing I really liked about the book was it didn’t feel super-heavy. You have a great way of blending in Southern comfort with political and historical takes. Was that something you went into the writing process conscious about or did it take several revisions and edits?

Aurielle: The thing about writing about Black folks is there’s no one facet of our reality. One part of our lives is enough for 10 books. You could write about this idea of Black joy or Black survival for a whole book, and that could be your whole career. The first version of Gumbo Ya Ya was definitely dark, and [had] an overwhelming amount of what I had been experiencing as a community organizer, as someone who had an experience of being kidnapped by the police. There was a lot of my anger, sorrow, mourning, frustration, exhaustion, and I’m even feeling heavy just talking about it.

That book still would’ve been true, and an honest depiction. But when I stepped back, I wanted to introduce a more vulnerable depiction of the stakes of Black life. And a more vulnerable depiction is that while people are shutting down the highway, somebody’s grandmother is making them a birthday meal. While people are saying her name, you know, some of us are graduating from college. While all of this deeply sorrowful, heavy stuff is going on, there are intersecting moments of joy, beauty, desire, right?

I remember being an organizer in 2015 and one of the things that all of the community organizers were talking about was this conference called Sex Down South, a conference about pleasure and sex — safe sex, expansive sex, queerness, all that. There you had all these organizers who had just been in jail, shutting down highways, putting on lingerie and latex to go and talk about consensual sex and pleasure! We truly contain multitudes.

Articulating the multitudes is really difficult and it’s also really vulnerable, because you want someone to believe you. I had to trust that my reader would believe me when I talked about how hard it was to go on after experiencing another death in our community, even though on the next page, I’m talking about twerking my ass on a dance floor when I was too young to get into the club. I had to trust that my readers had experienced that themselves, or could humanize me enough to honor me and my experiences.

Devyn: That’s really deep. If the reader doesn’t believe in you as a person then that will completely dictate how they receive and believe (or disbelieve) the poems and emotions. Two of my favorite poems from the book are right next to each other: Portrait of Rage With Caution Tape, and Bullhorns and War Strategies for Every Hood. Are there any personal favorites, where you feel like you really did what you had to do?

Aurielle: I think there are two battling it out for first place. I really love Pantoum for Aiyana. I think it’s actually the oldest poem in the book. The first time I started working on that poem was when Tamir Rice died. It was called “Hashtags,” and it had a whole different feel, a whole different vibe, and just wasn’t ready to be published.

It was missing something and it just stayed and grew with me. I’d go back and edit it every now and then, and after Aiyana Stanley-Jones was killed, I revisited it and was able to articulate things I had been feeling. You know, what happens when a Black child dies by the hands of police, and what that dynamic is like, how different that mourning feels. So that’s gonna always kind of stick with me.

The other is Poem of Failures, which is an honest, heartbreaking love poem to my dad. And I think it’s just for every Black girl and every Black child who has a complicated relationship with their dad, who recognize all of the context for how the world that affects me and the world that affects our relationship is also the world that affected him. Not to excuse the ways violence he experienced turned him into a violent person at times, but to offer vulnerability and nuance into our relationship. I’m not gonna say it’s his favorite poem, but it’s mine.

Devyn: Has your dad read the book?

Aurielle: I think my family and my dad in particular are hesitant and kind of intimidated by how honest the book tells our story. But I’m no more honest about me and my dad’s story than I am about the relationship between me and the state, the relationship between me and a lover, the relationship between me and the world. I don’t know if he’s ever gonna read it all, but you know, he’ll come when I do a little show and that’s enough for me.

Devyn: You said you’re born and raised in Atlanta, and there’s a love for Atlanta throughout the entire book.

Aurielle: I think the most Atlanta thing about me is that I don’t have to tell you I’m from Atlanta. People are always asking, are you from Atlanta? It’s not because my accent is heavy or because I sound like what they think people from Atlanta sound like, but I think that we carry ourselves a certain way. Like I carry Atlanta in my hips, you know, and this book is definitely one of those, “the girls that get it, get it, and the girls that don’t, don’t.”

If you didn’t sneak into Department Store on Edgewood with a fake ID or because you knew the bouncer, you don’t know what I’m talking about. If you didn’t get bean pies on Saturdays at the corner of Lowery and RDA, you don’t know what I’m talking about. If you didn’t take two buses and a train to get to school because your mama wanted you to go to a good school, you don’t know what I’m talking about.

This is a love story to Atlanta all up and through, because not only are there moments from the most beautiful parts of my city in the book, there are also very specific dynamics that I think are true in Atlanta more than they are true anywhere else. Like the idea of what it means to live in a Black city that creates Black wealth, at the expense of Black working class people. What it looks like to have an officer who is an agent of the state, but he looks like your uncle, or it might actually be your uncle.

It might be a very specific love story that can only be an Atlanta love story, because of all that Atlanta is. There are moments where I talk about playing outside and getting Georgia red clay on your jeans. And talking about the year they brought Freaknik back, and how if you lived in the city at that time all you remember is being near butt-naked people everywhere. Tailgating, partying in the city, all of those things. So if you crack open this book and you lived ITP at any point of your life, I hope you’ll feel at home, because that’s who and what I’m writing towards.

Dev: Any last words before we say goodbye?

Aurielle: Just that I think people get it wrong about poetry. There’s probably a lot of people who are gonna read this who aren’t into poetry, or don’t think they’re into poetry. I think, just like hip-hop is accessible to everyone, poetry is the same. Poetry is accessible to everyone, but it’s for us. And the proof is in the pudding at all parts of our history, all parts of our culture.