The Churn

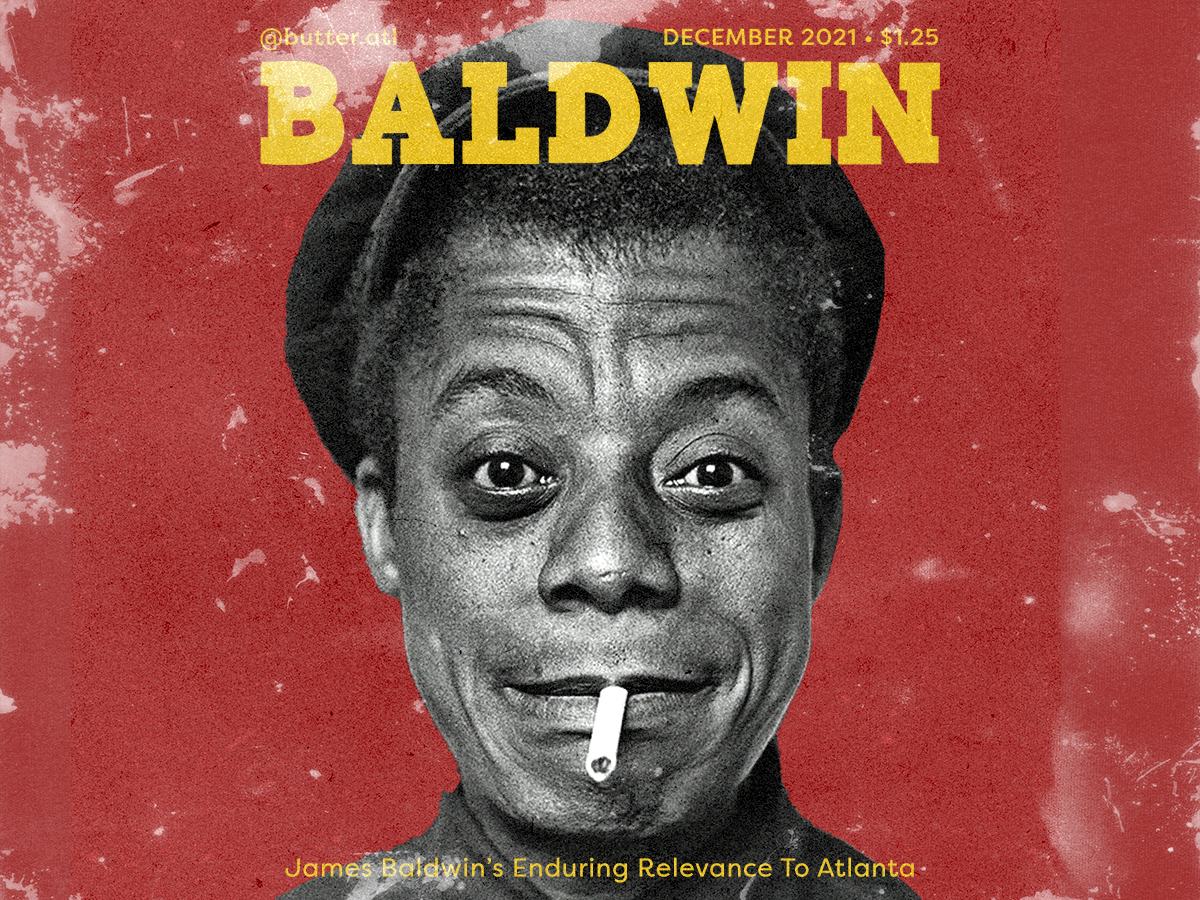

James Baldwin’s Enduring Relevance To Atlanta

Butter ATLDecember 1, 2021

“History, I contend, is the present—we, with every breath we take, and every move we make, are history—and what goes around, comes around.”

James Baldwin, The Evidence of Things Not Seen

James Baldwin, the famous Black American novelist, essayist, and playwright, died in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France on this day 34 years ago.

His work touched on everything from race, class, and sexuality to anti-war sentiments and gentrification, and his inimitable voice, style and ability to articulate America’s truths made him one of the most famous, recognizable writers of the 20th Century.

His nonfiction collections, like The Fire Next Time (1963) and No Name in the Street (1972), offer searing glances into the dark corners of American society, and give criticism to a country he saw as shaped by racism, profit, oppression, and violence. His novels tell stories with an enduring relevance, and you may remember the recent beautiful film adaption of his 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk by director Barry Jenkins.

When one thinks of Baldwin, one tends to think of Harlem, where he was born and wrote extensively about, or France, where he famously emigrated later in life.

But as it turns out, he has a brief yet influential history right here in Atlanta, too.

In 1979 Walter Lowe, Jr, the first Black editor at Playboy, called his literary hero James Baldwin in France to convince him to cover something that had began to capture the American public’s attention: the Atlanta Child Murders. As the story goes, Baldwin was a bit familiar with the situation brewing in Atlanta, but from all the way in France was unable to fully understand what was taking place, and did not agree to take the assignment until he learned that the Playboy editor on the phone with him was indeed a Black man.

For those needing a brief refresher, the Atlanta Child Murders were a series of disappearances of over two dozen Black children and teens from roughly 1979 to 1981. Many bodies of the disappeared children were found in rivers, the woods, or abandoned buildings. The paranoia and tension that such a harrowing tragedy placed on Atlanta almost caused the city to burst, as agitations began swelling between the majority Black communities in the city and the newly integrated police force.

Residents felt that the police hadn’t done their jobs to keep them safe; that what little answers they were eventually given around the case didn’t add up; that there were other cases that should have been included in the total count, and so forth. Enter Baldwin, a literary superstar of sorts by this point, who arrived at the Atlanta airport with booze on his breath and his own unique eclecticness.

Baldwin spent about two months in the city, refusing to simply repeat police press office narratives and the fiction of (at the time, at least) a post-racial “New South.” Instead he turned his focus on the lives of Atlanta’s Black community and Black children.

From this two month investigation — during which Baldwin went to numerous protests held by “The Committee to Stop Children’s Murders,” a local group formed by mothers of the missing children — a short but mighty book titled The Evidence of Things Not Seen was eventually published in 1985. This book, named after a Bible verse, may be one of his lesser read works, but it is one of his most indicting, poignant, and relevant works to date, especially for today’s Atlanta.

As activist Derrick Bell writes in the book’s foreword, Baldwin particularly “undertakes an exploration for truths” in the pages, as he’s most interested in what was exposed in the social, political, and racial dynamics surrounding the national tragedy. Baldwin examines the race relations of the newly-integrated, freshly “Black-led” Atlanta, the relationship between the police and the Black community, the “state of terror” he describes Black children living witihn, and eventually asserts that “the present social and political apparatus cannot serve human need.”

Looking through a similar lens as Baldwin, we are able to see what has fundamentally changed in the city too busy to hate, and what has remained painstakingly similar. In the opening pages, Baldwin lightheartedly pokes at the “stubborn and stunningly delusional” assertion we know too well: “I’m from Atlanta; I’m not from Georgia.” His point: the city’s “high visibility and commercial importance do not mean that Atlanta is not in the state of Georgia,” and in light of the trial, the “presence of a Black Administration” might not mean very much in terms of justice.

The infamous series of disappearances and murders have captured attention for years, and still have relevance today.

This past summer, outgoing mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announced her office had requested the case be reopened, to reexamine evidence and DNA related to the tragedy. In October, after over 40 years in an unmarked grave, Anthony Bernard Carter, who fell victim in 1980 at just 9 years old, was finally given a headstone. And just last month community leader and activist Michael Langford, who played an integral part in the investigation and memorialization of the Atlanta Child Murders, passed away, keeping attention on the case.

Baldwin arrived in an Atlanta which in some ways felt quite similar to the city’s current state. Folks in working class and Black neighborhoods were advised not to go outside alone, police seemed to be perched on every corner, and a curfew was put in place. People came into the city selling snake oil, psychic ability and other scams, looking to make quick bucks, and a sense of general unease fell over all the Peachtree streets. Talk of crime permeated all local media and was discussed heavily by virtually all politicians, and this talk materialized into what resembled a police state for some.

Today, we find Atlanta a hotbed of “crime,” at least if we let the media and politicians tell it. You can’t search “Atlanta news” on Google without reading stories about shootings, robberies, or petty theft.

“Crime” was in fact the most hot button topic in the recent mayoral campaign, coming off the heels of some notable, tragic events having taken place here. Baldwin indicts the system itself as a “crime” onto certain peoples, and I can’t help but wonder why crimes like what happened to Ahmaud Arbery or Anthony Hill are not as readily nor constantly spoken about by the same politicians.

It is hard to discuss the onslaught of crime reporting and occurrence in Atlanta without looking at the long arc of its history, especially standout events like the Atlanta Child Murders that mortified an entire generation of children and parents alike. Of course, there is a crime problem of sorts taking place in Atlanta and across the U.S. But, like Baldwin, I find it more useful to look at the bigger picture, and the historical and environmental factors at play.

Would we be so willing to pour millions into a new police training facility, for example, instead of examining the root causes of crimes (hello, inflation, housing crisis, and joblessness), if there wasn’t already a decades-laid groundwork of crime anxiety laid into the fabric of our memory? Would we so easily shrug away news that Atlanta’s the most surveilled city in the country, without deeply questioning what that really means in a Black-led city within a mass incarceration nation, without the original paranoia and anxiousness of this convict colony’s history?

James Baldwin’s relevance to this city is in exactly the questions he asked, the shadows he attempted to illuminate, and the answers he begs the readers to accept. He knew that no real examination of the present in this soulful city can stand without an exploration of history.

If we want history to continue moving forward, we have to pay attention to the evidence of things that are not seen, as the book’s title suggests, but what is witnessed, felt, and experienced. As Baldwin himself says, “My memory stammers: but my soul is a witness.”