The Churn

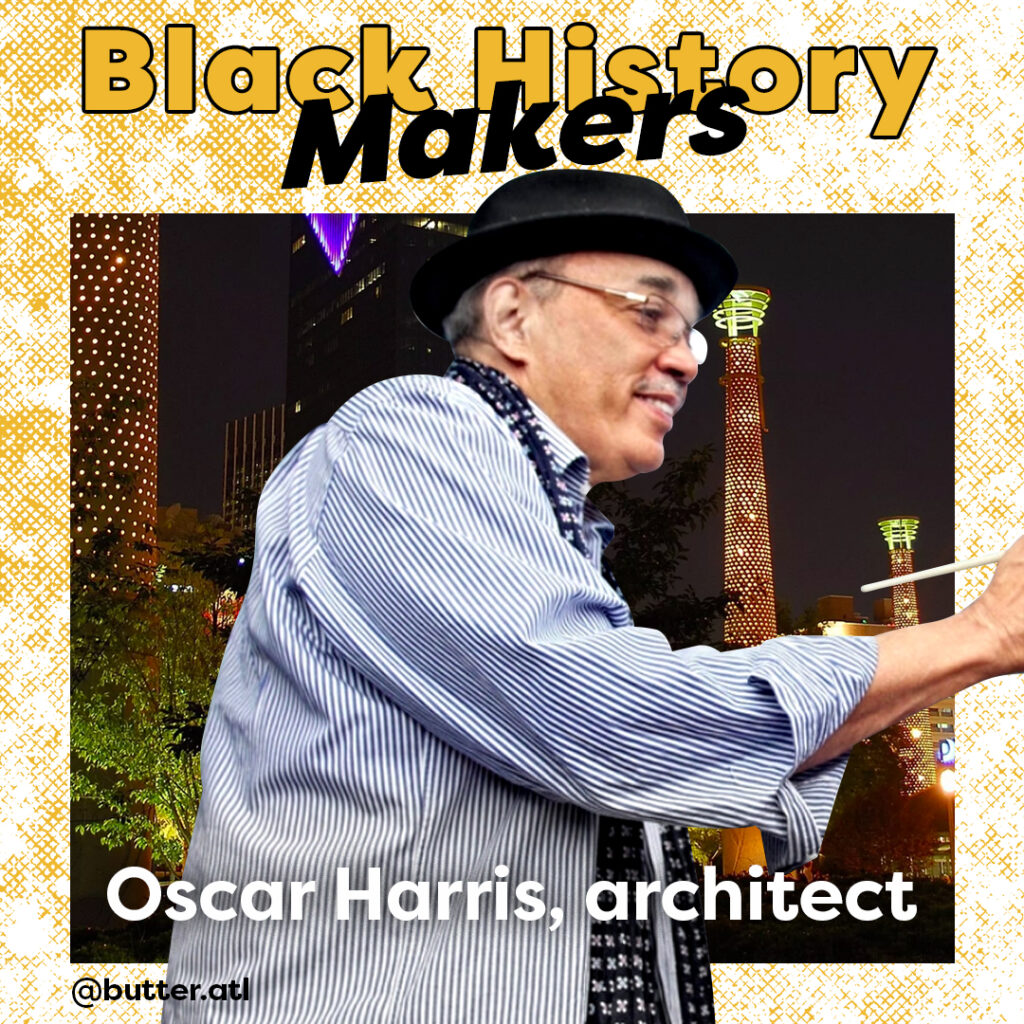

How Black Architect Oscar Harris Built Modern Atlanta

Mike JordanFebruary 25, 2021

The next time you find yourself on John Portman Boulevard in Atlanta, facing west toward Centennial Olympic Park, pay attention to the architecture. You probably already know that the gentleman for whom the street was renamed in 2012 designed much of downtown.

But John Portman didn’t design everything in the city. Actually, many of Atlanta’s most beloved and enduring constructions were designed by a Black man who spends time considering nature and art rather than worrying about having his own street.

His name is Oscar Harris, and if you love Atlanta you should know his name and salute his contributions to the city, and what he’s done with it, because his list of projects includes a wildly impressive list of ATL buildings, structures and landmarks you’ve surely seen and visited, but might’ve had no idea were conceived and overseen by an African-American.

Take his work on Centennial Olympic Park, for example. He calls it one of his all-time favorite projects from his multi-decade career as founder of Turner Associates Architects & Planners, which he launched in 1977.

“I did the towers that frame the park,” Mr. Harris says of the iconic crystal pillars flanking the park’s fountain of rings. “They sparkle at night. I’m proud of the way they still sparkle and represent the spirit of Atlanta.”

Maybe you’ve been to the world’s busiest airport? If so, you’re very familiar with Mr. Harris. He not only designed and oversaw construction of Concourse E of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, but also its centerpiece, the atrium that lets natural light pour in from above.

You’ve also seen his work at Zoo Atlanta, Underground Atlanta, Georgia State’s student center, the Fulton County Government Center, Kilgore Student Center at Morehouse, multiple MARTA stations (Doraville, Perimeter, Hamilton E. Holmes, etc.), and even detention centers. All in all, Turner Associates has put more than $3.5 billion in completed projects in the ground in Atlanta.

You don’t get those kinds of responsibilities being decent at your job. You had to not just be great — you had to be the best, and that’s what Mr. Harris decided to be early in his career.

“My whole thing was to be the best in Atlanta,” he says. “You had African-American firms that were very good — J.W. Robinson and others — but I just worked on being the best. And what happened is that they’d want you to work on stuff. Everybody would come to you. You didn’t need to run around saying you were the best, and didn’t have to go on the internet and pump yourself up — everybody knew it.”

A native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Mr. Harris is a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA), a highly prestigious title which less than 4 percent of all architects in the U.S. can claim. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Lincoln University, the nation’s first degree-granting HBCU.

Math wasn’t his original plan for college; he just found himself needing a major and picked one. “My parents said I needed a general education, so that’s why I went to Lincoln. I didn’t know until senior year what I was gonna major in. I didn’t like math very much — I was only like a C student — but I had a skill in drawing and arts.

“I told my mother, and she said ‘Lord, no. You can be an artist but do it as a hobby. Find something you do the very best and no one can do better than you, and focus on that.’ That’s what got me in architecture. It was a little bit of math and I was making art pieces, and it came together.”

He then went to Howard University to study architecture, which he enjoyed because of the high expectations for excellence and professionalism in his field. His Black instructors were also FAIA, and insisted on best-in-class work.

“They taught me how to put a building together,” he says, “and the D.C. places would hire you because you could produce documents.”

He left Howard and moved back to Pittsburgh for love (his girlfriend Sylvia still lived back home), and to attend Carnegie Mellon University, where he the first African-American to attend the school for architecture at the master’s level. He says being a first at the prestigious school was also critical for his education, but not just because of the schoolwork.

“All I saw was the majority population. Those folks were the tops of the tops, so I had to show them what I could put down. And that’s what I did; I became the best at doing it.”

Architecture is a very prescriptive thing, Mr. Harris says, and it’s the thinking process that he loves most.

“My philosophy is one of getting your mind cleared out and being open to what you hear and see. You observe through your two eyes what you see with your third.”

He says Concourse E at the airport is another one of his favorites. He was the prime architect for the whole concourse, from end to end, even overseeing the artwork to ensure that the city makes a good first impression for visitors from near and far.

“If you go out there,” he says of Concourse E, “there’s not supposed to be advertisement — just art. The reason is we have a lot of international travelers come through there. When they come to Atlanta, we want them to feel good and warm.”

Mr. Harris spends a lot of time in nature, taking walks in the woods by himself to remove distractions, observing how and why things are in place. Once he’s felt the energy of a space come through him, he makes decisions and is able to work those insights into his designs. That’s why he likes being on the front end of projects, as the prime architect as opposed to a contractor. That’s where the energy is.

“You get excited when you start. You think, ‘How am I gonna lay this thing out?’ You go to bed, wake up thinking about it. And that zone is the beginning — the conceptualization. That’s what I really enjoy.”

These days his time is almost exclusively spent with his wife, children and grandchildren, along with painting and fine art. He also spends a great deal of time leading the Atlanta Center for Creative Inquiry, which he founded in 2004 to mentor, educate and inspire high school students to enter architecture, construction and engineering.

To date, Mr. Harris says the Center has reached about 500,000 students, plenty of them going into the field to help design the future.

And he’s still thinking and making, although that’s mainly in the form of painting and fine art, which he’s fond of creating after one of his beloved walks through the woods and being in the presence of nature.

His paintings are available for purchase, but he doesn’t accept commissions, because when you’ve been as successful as Oscar Harris at turning an idea into reality, you get to make the choice and design your day.

“I make anything I wanna make,” he says. “I don’t work for anybody. I produce.”

Oscar Harris, FAIA, is leading a free virtual student empowerment and community impact workshop on Saturday, February 27. Register and attend it on Zoom by clicking here.