The Churn

A Look at Instagram’s Underground Food Economy, Through The Lemon Pepper Wet Pizza

Mike JordanOctober 27, 2020

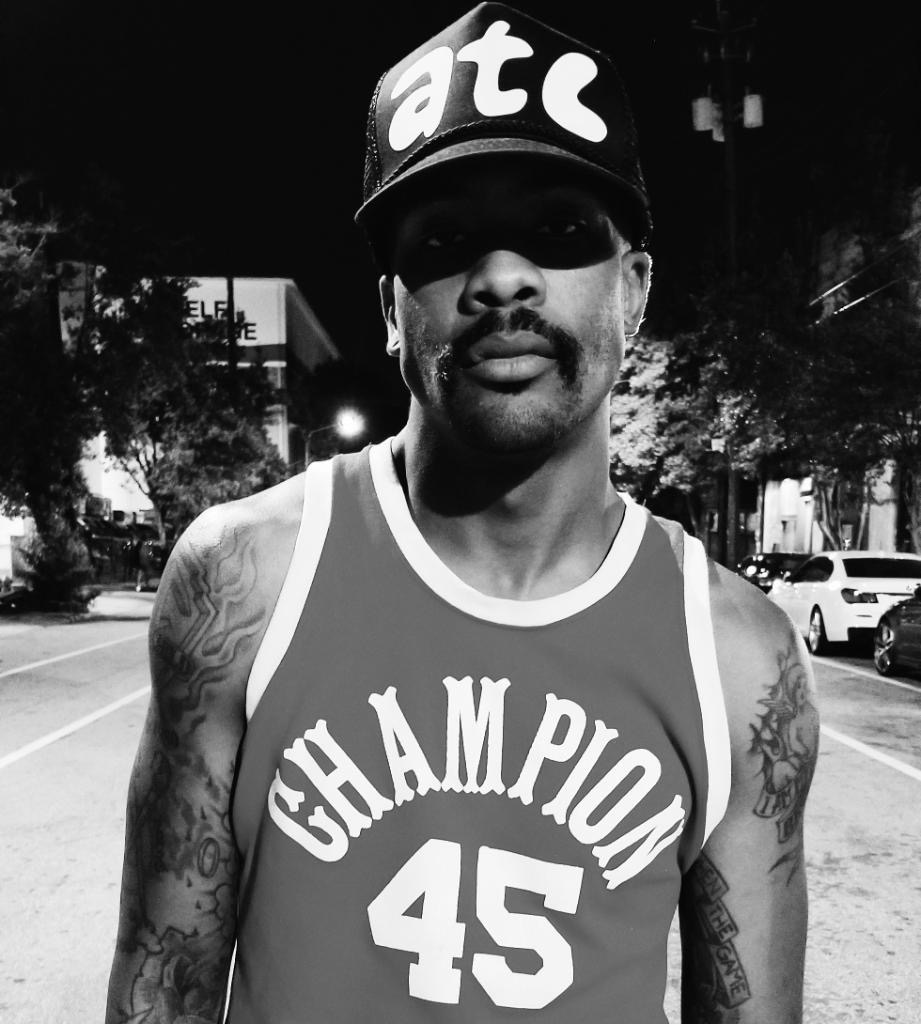

“I put all of me into my pizza and Phew’s Pies,” Matthew “Phew” Foster says. “Phew’s Pies is Atlanta.”

Phew is the founder and owner of Phew’s Pies. He has neither a restaurant nor a catering business (yet), but with his Lemon Pepper Wet pizza, which you can order through Instagram, he has a certified Atlanta hit.

The 12-inch pizza is made with butter sauce, mozzarella cheese and chopped chicken, and as a finishing touch, comes with two lemon pepper wings sitting on the center. It’s as ATL as a pizza can get.

“It embodies the flavor of the city in a way never done before,” Phew says of his edible invention. “It also shows the possibility of two different culinary styles working together to produce something dope, fun, tasty, and new, while staying true to their roots.”

I followed the protocols to order the Lemon Pepper Wet pizza on Tuesday, October 20, placing my order via text, which was confirmed once Phew received payment via CashApp.

I was then given an option to say when I wanted to pick up my pie. I requested 8pm, and texted when I pulled up to the curb at Phew’s given address. Don’t look for it on Google Maps; just trust us — it’s in a neighborhood on Atlanta’s westside.

Phew meets me in the middle of the street, wearing a mask. The pizza box is warm, and he’s just as friendly, thanking me for my business. After a 10-minute drive home, I open the box and tear into a slice.

TL;DR Review: It’s a surprisingly solid pizza — on par with (and maybe better than) lots of local pizzerias in Atlanta.

Phew’s Pies’ menu has traditional pizzas (pepperoni, veggie, etc.) for $12 or less, while higher-priced specialties like the Lemon Pepper Wet, are $30 or close. Phew uses a portable gas oven to bake the pizza, and universal kitchen tools like the Instant Pot and an Air Fryer for food prep.

For $10 extra, you can get any pizza “In(phew)sed,” with 40mg of “raw THC, tincture and cannabutter.” Phew says business is booming.

“So far on my own, I’ve pulled in $11-13k a month in revenue,” he says. “With growth and expansion, I plan on doubling these numbers in 2021.”

Phew is definitely on the bolder side of a business model that’s still not exactly regulated. Selling home-cooked meals on Instagram was already a thing before COVID-19, but has become much bigger since restaurants have been made to close or function at limited capacity.

People like Phew are on the frontlines of a battle for what might be the future of the food and beverage industry. And just like it sounds, it’s a virtual Wild West of culinary capitalism.

Atlanta food influencer Gourmetangiie (yes, with two “i”s) didn’t launch her Instagram profile with a big celebrity endorsement back in September 2019. It started simply, with a closeup video of a steak, plated with asparagus and sweet potatoes, which received 941 views.

13 months later, Gourmetangiie LLC has more than 7,500 IG followers, thousands of video views, and enough paying clients to keep her busy all week. Without going into detail, it’s an income opportunity she describes as “lucrative.”

She says things got serious when she posted a video of her creamy mac and cheese, which has received more than 3k likes since April.

She uses IG mainly as a marketing channel for private bookings, but also has paid partnerships ranging from restaurants and bars to hot sauce companies and cutlery brands.

She also sells recipes for dishes like Hennessy honey-glazed salmon for $5, and has offered weekly meal prep for dishes like coconut curry shrimp through her DMs.

“When people go on my page, I’m just highlighting good food, whether it’s from my kitchen or your kitchen, a restaurant kitchen, or even like small upcoming businesses.”

Born in Canada, with Jamaican, German and Guyanese ancestry and a childhood spent in Louisiana, Gourmetangiie uses her appreciation for multiculturalism to fuel her culinary curiosity.

She also leans into family recipes, such as her late grandmother’s fried escovitch red snapper, which is her personal favorite thing she cooks and which she loves to share.

“It makes me happy that I can tap in with my culture and, you know, just feed other people the food that I grew up on.”

Instagram chefs have operated in a gray area, in terms of law, and that’s before weed butter started getting mixed into pizza dough.

Angiie says IG cooks who avoid addressing the legalities still must realize customers have to feel reassured about food safety before they’ll buy the food, much less bite into it.

“Like anything you put out, you want to do the best and have the best quality,” Gourmetangiie says. “You can’t just be out here giving people any kind of thing.”

“Also, I’m licensed. I have a food permit so I can serve people. You definitely want to get your business licenses, your LLC, things like that. If you don’t have that, that’s kind of where you run into problems.”

Chef Scotley Innis says anyone selling meals from their home kitchens, especially on social media, needs to be careful in more ways than one.

Innis is former executive chef at Atlanta restaurants Ormsby’s and 5Church, and a former contestant on season 18 of Hell’s Kitchen.

He currently runs a carryout-only Jamaican restaurant called Scotch Yards, and has another restaurant being built on Atlanta’s Buford Highway, scheduled to open by year’s end.

“It’s a negative and positive thing,” Innis says about social media as a food marketplace. “It’s a free marketing tool that reaches people faster than any advertisement. Once people go on their phones, they’re on a social media platform.”

Innis says he used social media at 5Church on days when he’d have dinner specials.

“I might post it before the dinner rush,” he says. “That way, if we didn’t have reservations already, people would see [the food], and it attracts the clients.”

He says home cooks becoming overnight sensations isn’t automatically bad, but he isn’t fond of those who let social media recognition, rather than training or experience, convince them they are chefs.

“Chef titles are very sacred. I know what it took for me to earn that title. So for it to be thrown around on Instagram, it bothers me. I’ve been on national TV — Hell’s Kitchen and all that. I don’t have 10,000 followers. But I don’t take it as I’m not as known as someone who has 60,000 followers and is not a chef.”

Innis also isn’t sure IG cooks and customers are thinking about the other downsides to unregulated restaurateurship.

“You have no idea how people store their food, how they cook their food. Is it sanitary? Did they wash their hands, cutting boards and knives, so there’s no cross-contamination? It’s hit or miss.”

To be clear, there are different rules in different states in terms of what home cooks can sell to the public, with California seemingly ahead of other states in terms of what is allowed.

Here in Georgia, the Department of Agriculture is clear that only a small list of “non-potentially hazardous foods” qualify for legal sales under the Cottage Food Program. Baked goods and things that can be kept at room temperature tend to be fine; things that require refrigeration, not so much.

Gourmetangiie’s profile page says she’s a “SERVSAFE private chef,” and Phew says he’s got the same credentials.

“We are ServSafe-certified and have been trained on the COVID-19 food and beverage handling regulations and guidelines. All orders are prepared with the use of disposable gloves and masks. Thankfully, we have not had any issues surrounding food safety from our customers.”

Innis thinks too many culinary entrepreneurs are more concerned with likes, views and impressions than the risks, repercussions and fines. That recognition from going viral, he says, could backfire because one angry/dissatisfied/sick customer files a complaint, bringing the whole operation down.

“But everybody has to hustle,” he says. “It’s the underground restaurant world. I can’t say that I haven’t done it before, you know?”

Phew is definitely in hustle-mode, and nowhere near ready to slow down on. He’s starting an online ordering service separate from IG at PhewPies.com, which he says will be ready around Halloween.

He says he has a three-tiered plan to open physical restaurants and mobile pizza services as Phew’s Pies evolves. He also wants to eventually source all of his produce from Black-owned farms.

And he’s not willing to look back at where he was before the Lemon Pepper Wet pizza blew up.

“I’ve tried, failed and given up on lots of dreams or endeavors of mine. Each and every time I would think or speak in a negative light about the situation,” he says. “The only thing I’ve never talked bad about has been pizza.”

Take that positive energy, coming from a former food runner at Atlanta pizzeria Ammazza, and add self-determination, perseverance and culinary talent, and it’s hard not to hope Phew and all the other dreaming cooks of Instagram make good on their goals.

“What pushed me to do this, besides sheer passion for pizza, was the want for inclusion. Few and far between do you find a black-owned pizzeria in this country. The numbers are slimmer in the south,” Phew says.

“I decided the south got something to say. Black pizza got something to say. And in the midst of the worst year in human history, during a global quarantine and financial crisis, I started a business, thanks to dedication, hard work, plus patience.”